Key Takeaways

-

The introduction of highly attractive (i.e., fewer night shifts) employment opportunities for providers in an increasingly disintermediated health economy is an additional constraint on the already shrinking supply of physicians, exacerbating the ongoing primary care challenges facing the health economy.

-

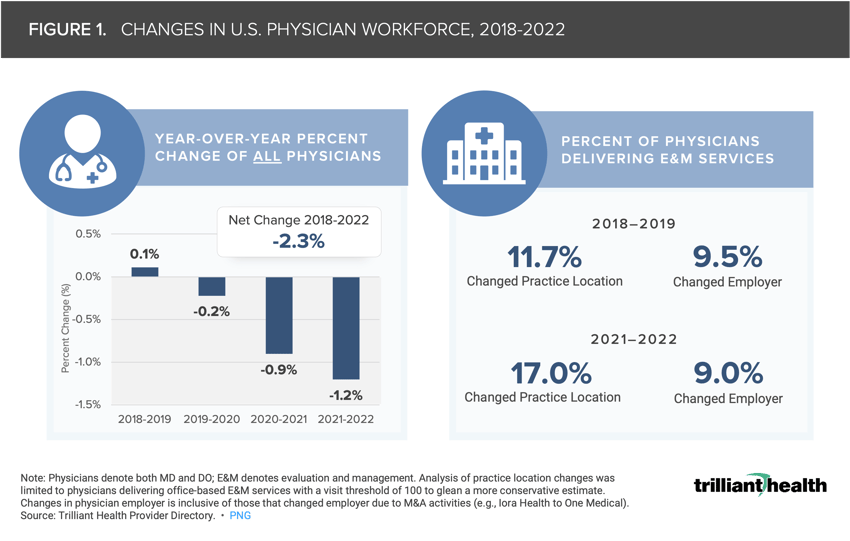

The net number of physicians that started and stopped practicing between 2018 and 2022 resulted in a -2.3% workforce reduction, and fewer providers are being employed by traditional health systems. These changes reflect the impact of geographic relocations (i.e., from one health system to another), changes in practice type (i.e., traditional to retail provider), and “moonlighting” across organizations, particularly among those with virtual offerings.

-

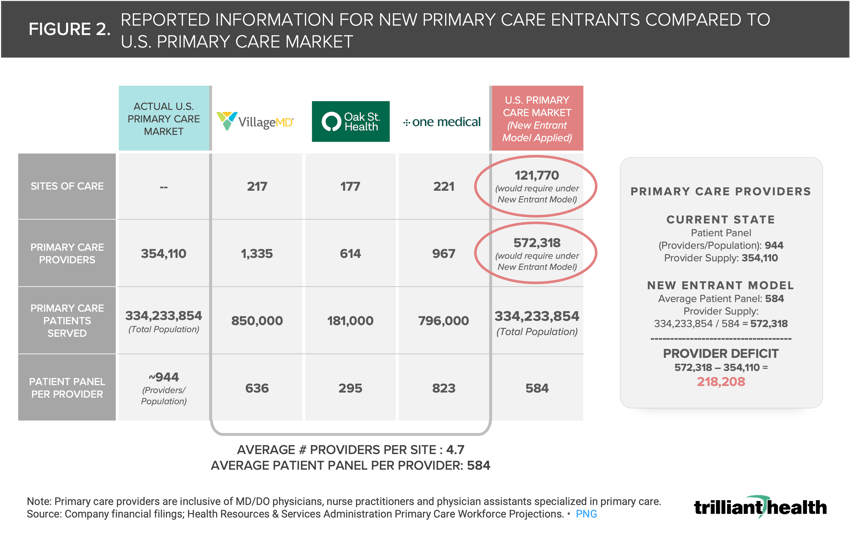

The patient panel for new primary care entrants averages 584 patients per provider, suggesting that the U.S. would need an additional 218,000 primary care providers to meet the needs of every American under this model.

Recently, we have explored the dynamics of disintermediation in healthcare resulting from the on-demand, consumer-centric care provided by new entrants like CVS, Walmart and Amazon.1 Despite expanding care options, these new entrants are disintermediating the traditional healthcare journey by funneling patients into a closed-loop, retail-pharmacy-enabled system.2 Moreover, consumer preference for convenience-based care is poorly aligned with the coordination of care that providers, payers and employers have historically deemed important.

There are now more providers of care competing for the consumer’s loyalty, a declining share of whom are commercially insured.3 Most research on the retail-based primary care models has focused on consumer loyalty and corresponding market share implications for providers, with less consideration of the supply side impact of increased primary care access points.

Health systems and traditional providers have historically faced workforce issues (e.g., an aging workforce, burnout), which the pandemic and ensuing Great Resignation worsened.4 Traditional providers must compete for the shrinking pool of talent against life sciences organizations, payers, consulting firms, consumer goods companies and, now, retail-based providers. The retail-based entrants offer competitive salaries, benefits, incentive-based compensation and appealing flexible and hybrid work schedules as compared to traditional provider environments.

The introduction of highly attractive (i.e., fewer night shifts) employment opportunities for providers in an increasingly disintermediated health economy will likely further constrain the already shrinking supply of physicians, exacerbating the ongoing primary care challenges facing the health economy.

Organizations Are Competing for a Shrinking Number of Providers

Understanding the extent to which new care models are constraining supply requires a baseline of preexisting staffing shortages. While burnout has been present for years, the COVID-19 pandemic compounded workloads and heightened frustrations, accelerating a decline in supply of clinicians. To date, efforts to bolster the provider workforce have not moved the needle.

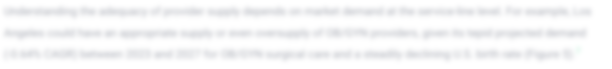

Leveraging our Provider Directory, we identified changes in national physician practice patterns and found that the net number of physicians that started and stopped practicing between 2018 and 2022 resulted in a -2.3% workforce reduction (Figure 1). Notably, 9.0% of physicians that deliver E&M services changed employers from 2021 to 2022. These changes reflect the impact of geographic relocations (i.e., from one health system to another), changes in practice type (i.e., traditional to retail provider) and “moonlighting” across organizations, particularly among those with virtual offerings.

As New Primary Care Models Scale, Provider Supply Will Be Further Constrained

The retail-based care model appeals to both providers and patients, but it is unclear whether retail and direct-to-consumer (DTC) models can scale to meet the needs of every American.5,6 Under a traditional primary care model, the typical panel is 944 patients per primary care provider (i.e., MD/DO physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant specialized in primary care). In contrast, the patient panel for new primary care entrants is much lower, averaging 584 patients per provider. Scaled nationally to the U.S. population (334M), the new entrant primary care model would require a total of 572,318 primary care providers (Figure 2). Relative to the current state, this suggests that the U.S. would need an additional 218,000 primary care providers to meet the needs of every American under this model.

Are more Americans using primary care than previously? No. Has the health status of Americans improved? No, in fact it is worsening. Are Americans engaging in more preventive care despite having more access to care with respect to insurance coverage and more convenient options, whether it be virtual or retail? Not at all.

Aside from consumer convenience and provider preference, what benefits do retail-care based models offer to the ailing U.S. healthcare system, particularly with respect to value for money?

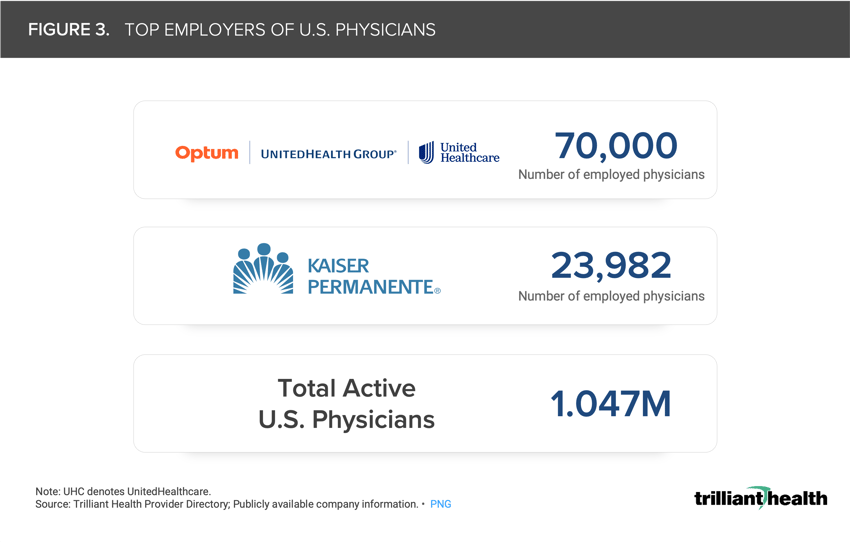

While new entrants have a significant footprint in the health economy, health systems as a collective stakeholder remain the largest employer of physicians and two large "payviders” — Optum and Kaiser Permanente — are the two largest employers of U.S. physicians (Figure 3). While provider supply continues to shrink, competition for the remaining healthcare professionals will continue to intensify.

Health systems and other provider entities must develop new strategies to support recruitment and retention to adequately serve their markets and compete with new entrants, especially in an environment characterized on one hand by a growing burden of disease and on the other by declining demand for and utilization of primary care, fragmentation, commoditization, lower trust, higher costs and low operating margins.

What policies and initiatives are needed to re-engage the workforce and build a stronger culture for clinicians? Could collaborating with clinical societies to better align scope-of-practice criteria with delivery standards improve retention? Could modernization of clinical education requirements and reduced program length ensure a steady influx of skilled professionals?

How will market consolidation impact provider supply, especially as demand declines and hospitals close entirely or shutter inpatient units (e.g., maternity care)? How will patient perception of quality across primary care access points impact demand? Can retailers deliver primary care models with more scale (i.e., higher throughput) and with higher consumer satisfaction than traditional providers? Will consumers understand and appreciate the difference between the historic longitudinal relationship with a primary care provider and the transactional relationship with a retailer? Health economy stakeholders must consider the implications of these questions and potential downstream impacts.

Even so, healthcare is local, and understanding market-level dynamics is essential for developing strategies to address workforce supply challenges. Log in to the Compass+ platform to continue reading.

Undersupply and Oversupply of Physicians and Allied Health Providers Varies Across Large U.S. Markets

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)