Research

Minnesota's Novel 340B Financial Reporting Program Reveals Revenue Concentration Among Disproportionate Share Hospitals and Specialty Medications

August 25, 2025Study Takeaways

- Minnesota's 340B Program was associated with $630M in net revenue in 2023 for all covered entities, with 80.2% concentrated among disproportionate share hospitals.

- Three medical centers account for 45% of the state's total 340B net revenue.

- Commercial insurance generated the largest proportion of revenue (54.4%), followed by Medicare (31.3%).

- Revenue from the 340B program is primarily driven by low volume, high-cost specialty medications such as Humira®.

The 340B Drug Pricing Program (the 340B Program), established through Federal legislation in 1992, mandates discounted medication pricing for qualifying provider organizations that disproportionately serve vulnerable populations. Despite substantial expansion since inception, opaque operational mechanisms have led to documented instances of noncompliance, duplicate discounting, financial inefficiencies and insufficient oversight, creating challenges across the pharmaceutical supply chain and potentially undermining the program's intended benefits. Today, the 340B Program is a significant revenue source for many U.S. not-for-profit hospitals.

The opacity about the financial aspects of the 340B Program exists amid growing system-wide emphasis on healthcare transparency, exemplified by CMS’s Transparency in Coverage initiatives about price transparency. Consequently, the 340B Program faces scrutiny from regulators, policymakers, health economists and the life sciences industry. The introduction of corresponding 340B transparency requirements would make data-driven analysis regarding program effectiveness and the identification of associated improvement opportunities a possibility.

Background

The 340B Program enables qualifying hospitals and clinics (i.e., covered entities) that serve a significant uninsured or low-income population to acquire outpatient medications at reduced costs. Program eligibility has expanded considerably since inception, particularly following the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Eligible providers now include disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), federally qualified health centers, children's hospitals, critical access hospitals (CAH), specialized clinics and Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grantees. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of 340B covered entity sites grew from just over 8,100 to 50,000, with a major increase after 2010 due to expanded eligibility, especially among CAHs.1 Prior to 2004, hospitals accounted for less than 10% of covered entities but this proportion has grown to more than 60% as of 2020.

Notably, 340B Program eligibility for DSH hospitals requires a disproportionate share percentage greater than 11.75%. Of the roughly 6,000 U.S. hospitals, 2,464 (41%) are considered DSH hospitals.2 Additionally, nearly half of DSH hospitals (48%) are actively eligible for the 340B program.3

Manufacturers must participate in 340B to engage in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, selling medications at the "340B ceiling price." Certain products including vaccines, orphan drugs and medications purchased through group purchasing organizations remain ineligible for discounting. Program regulations stipulate that covered entities may only dispense 340B-discounted medications to patients with established institutional relationships, though patient eligibility criteria remain broadly defined. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) oversees implementation of the 340B Program and is responsible for audits of covered entities and pharmaceutical suppliers.

In 2023, 340B purchases totaled $66.3B nationwide, with 78.3% associated with DSH hospitals.4 The program represented 8.7% of the total U.S. pharmaceutical market in 2022.5 Participating entities may directly purchase medications at discounted rates or secure retroactive rebates following full-price acquisitions. Entities without in-house pharmacies may utilize contract pharmacies, with over 25K such arrangements in place in 2022, predominantly involving major retail chains including Walgreens, CVS, Walmart and Rite Aid.6

Despite increasing bipartisan scrutiny of the 340B Program in recent years, no meaningful reform of the 340B Program has been implemented.7 Congress is intensifying its oversight of the 340B Program through both legislative and investigatory actions, signaling growing concern over how hospitals use the program’s savings. Coupled with the first-ever 340B transparency bill advancing out of a House committee and other ongoing legislative efforts, the scrutiny suggests a shifting landscape — one where Congress appears more willing than in years past to reform and regulate hospital participation in the 340B Program.

While Federal laws don't require public 340B financial reporting, three states – Maine, Minnesota and Washington – mandate public financial disclosures. Minnesota's 2023 transparency law requires covered entities to report financial information including costs, revenues, program operations, fund usage and arrangements with contract pharmacies and third-party administrators. This analysis utilizes the Minnesota transparency law to examine characteristics of 340B spending.

Analytic Approach

The 2024 Minnesota Department of Health 340B Covered Entity Report was leveraged to analyze 340B net revenue distribution across different covered entity types and payer sources, revenue concentration among select covered entities and revenue from specific medications and their associated per-fill revenue.8

Findings

In 2023, 340B net revenue at covered entities in Minnesota totaled approximately $630M. Similar to the national distribution, DSHs accounted for the largest share of 340B net revenue (80.2%) across all payer types in Minnesota, with particularly high revenue coming from commercial payers and Medicare, both of which count against Medicaid DSH eligibility. Across all covered entities, 54.4% of revenue was from commercial patients, 31.3% from Medicare, 13.7% from Medicaid and 0.5% from other payers (Figure 1). While most revenue for hospital covered entities stemmed from commercial insurance, most revenue for disease-specific Federal grantees and safety-net Federal grantees came from Medicaid.

📌 The graph below in interactive. Hover over the bar(s) for more information.

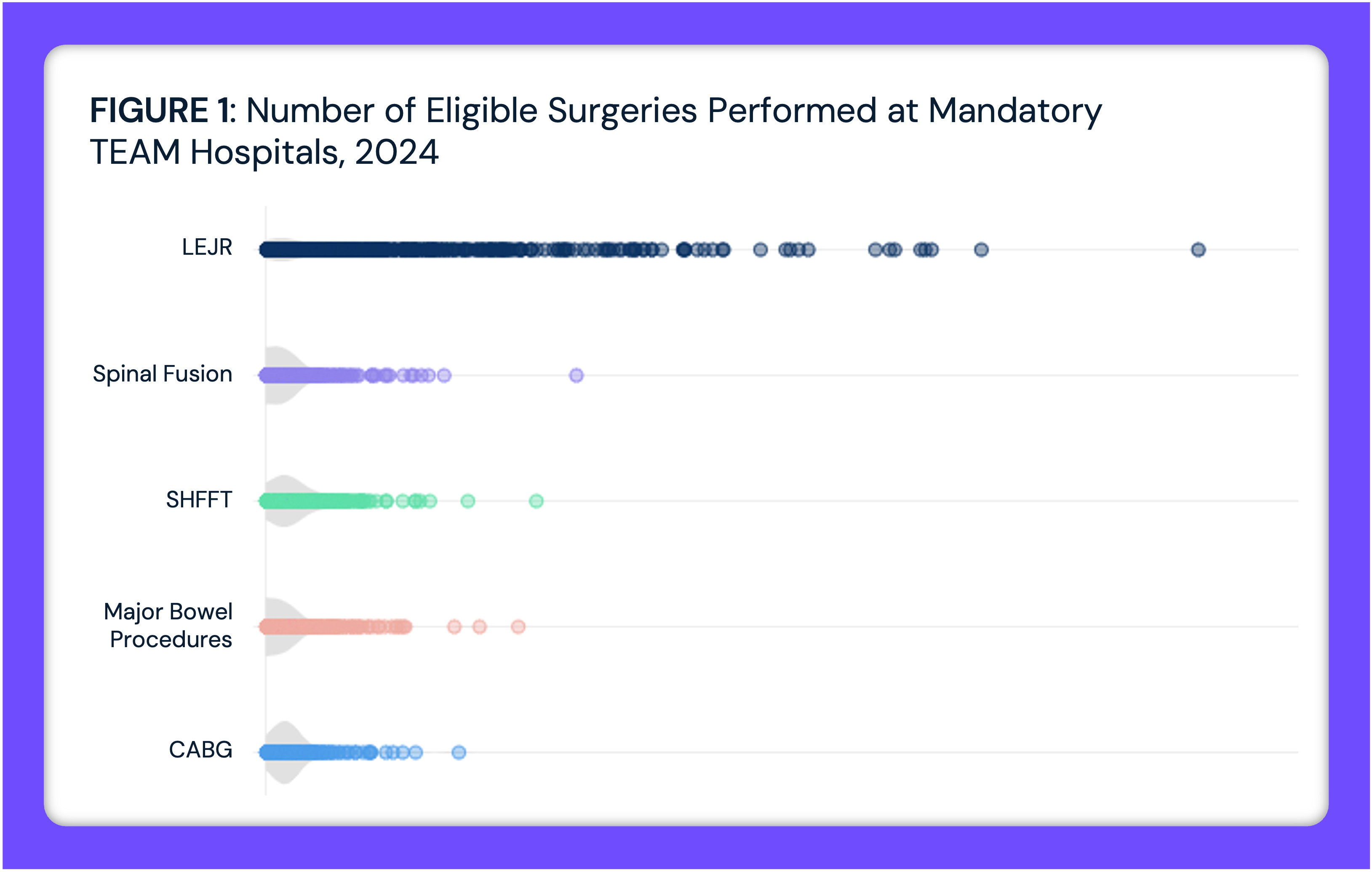

In 2023, the $630M net 340B revenue in Minnesota was concentrated among a few covered entities. M Health Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center accounted for the highest portion of statewide net 340B revenue at 21% ($129.6M), followed by North Memorial Health Hospital (13%, $80.1M) and Hennepin Healthcare (11%, $70.2M) (Figure 2), while disease-specific and safety-net providers such as Children’s Minnesota Comprehensive Hemophilia Disease Treatment Center ($13.9M, 2%) also generated significant 340B revenue.

📌 The graph below in interactive. Hover over the dot(s) for more information.

In 2023, the highest revenue drug categories at Minnesota 340B covered entities varied significantly in both total net revenue and average revenue per fill, with biologics and other high-cost therapies driving the largest share of revenue. Prescriptions for Humira® (Adalimumab) generated $12.2M in net revenue across 3,593 fills, followed by Trikafta® (Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor) at $9.7M across 2,465 fills (Figure 2). Despite 17,335 total fills, Eliquis® (Apixaban) ranked third in total net revenue at $9.7M, because of its lower average revenue per fill ($558) compared to biologics.

Drugs with fewer fills but high per-fill revenue include Kineret® (Anakinra), which had 181 fills but the highest average revenue per fill at $8,066, and Enbrel® (Etanercept), which generated $3.9M from only 578 fills at $6,747 per fill. Additionally, Nexviazyme® (Avalglucosidase Alfa-ngpt), used for Pompe disease, had only 68 fills but generated $2.66M in net 340B revenue, resulting in comparatively high average revenue per fill of $39,156.

In contrast to high-cost specialty medications that drive overall 340B net revenue, the most frequently filled drugs in hospitals do not significantly contribute to total revenue. For example, oxycodone, the most frequently filled drug, had over 80,000 fills but generated only $100K in 340B net revenue. Fentanyl ranked ninth by volume, with 20K fills and $360K in revenue. Similarly, common hospital drugs such as acetaminophen, sodium chloride and ibuprofen are among the most frequently dispensed 340B medications but generate only $1 to $30 per fill, with none exceeding $1M in total revenue. This contrast highlights how high-volume, low-cost medications primarily serve patient care needs, while specialty and biologic drugs disproportionately drive total 340B revenue.

📌 The graph below in interactive. Hover over the dot(s) for more information.

Conclusion

The 340B Program continues to remain a component of the U.S. healthcare system, influencing a portion of not-for-profit hospital revenue, with stakeholders expressing divergent perspectives on the program’s impact. While hospitals and other covered entities emphasize the program’s role in expanding access to affordable medications and offsetting financial losses associated with uncompensated care, pharmaceutical manufacturers and policymakers have raised concerns regarding its oversight, lack of transparency and adherence to its original intent of lowering patient financial burden. The absence of restrictions on revenue utilization, coupled with limited reporting requirements, calls into question whether the 340B Program benefits directly support vulnerable populations or simply contribute to institutional profit margins.

As a result, the 340B Program has faced numerous regulatory and legal challenges, with HRSA audits identifying over 500 instances of drug diversion between 2012 and 2020. In turn, manufacturers have imposed stricter controls, such as limiting the number of contract pharmacies and requiring extensive claims data submissions.9 However, court rulings have pushed back against restrictive manufacturer-imposed measures, seemingly reinforcing the expansion of the 340B Program beyond its original scope. Even so, ongoing investigations into the role of contract pharmacies and pharmacy benefit managers could lead to further regulatory adjustments aimed at preventing misappropriation of 340B savings. However, in the absence of Congressional action, the 340B Program is poised for continued growth, particularly as an increasingly sicker U.S. population will drive increased demand for high-cost specialty medications, such as oncology drugs.

More importantly, specialty (e.g., Humira®) and high-cost (e.g., GLP-1s) drugs are increasingly serving as effective substitutes for surgical interventions. As such, the 340B Program could be a modern-day Trojan Horse, with the current revenue generation from the program masking the looming wholesale replacement of hospital-based interventions in favor of specialty pharmacy prescriptions. Health economy stakeholders should consider the ramifications of such a scenario, ranging from the cost implications of one-time surgical interventions versus the duration of the substitute pharmaceutical interventions to the risks associated with powerful, but novel, therapies without long-term outcome histories.

- Studies

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)