Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | November 1, 2023How Elon Musk Might Transform the U.S. Healthcare System by Applying Insights From First Principles, Farm Analogies and Football Coaches

Elon Musk is widely known as an adherent of first principles, which he has synthesized into the “Musk algorithm”1:

- Question every requirement

- Delete any part or process you can

- Simplify and optimize

- Accelerate cycle times

- Automate

In this interview, Musk stated:

"I think it’s important to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. So, the normal way we conduct our lives is, we reason by analogy. We are doing this because it’s like something else that was done, or it is like what other people are doing… with slight iterations on a theme. And it’s … mentally easier to reason by analogy rather than from first principles. First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world, and what that really means is, you … boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say, 'okay, what are we sure is true?'… and then reason up from there. That takes a lot more mental energy.”

In last month’s Counterpoint, I referenced the power of the status quo in the health economy, “manifesting quietly in the form of lazy heuristics, reasoning by analogy and reliance on the ‘things we know’ instead of facts.” The health economy is replete with examples of these habits, so I will highlight five of the most value-destroying examples:

1. Employer-sponsored health insurance. Joseph Schumpeter stated that “history is a record of the ‘effects’ the vast majority of which nobody intended to produce,” and there is no better example than employer-sponsored health insurance, the “elephant in the room” of the U.S. healthcare system. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no part of the U.S. health economy is more reflective of the status quo than the way that human resource departments administer employer-sponsored health insurance. Peak status quo manifests annually during “open enrollment,” in which employers, relying on sensitivity analyses prepared by benefits consultants, shift as much of the ever-increasing cost of health insurance to employees without creating an insurrection.

The catalyst for the growth of employer-sponsored health insurance was the War Board’s 1943 decision to exempt employer-sponsored health insurance from the wage freeze introduced by the Stabilization Act of 1942, ironically as an effort to prevent labor groups from striking.2 Avoiding a strike is clearly inconsistent with designing health insurance from a first principles approach, which would initially question the necessity of health insurance to facilitate a value exchange between an individual and a provider of healthcare services. If a first principles approach determined that such a value exchange required an intermediary, the employer seems to be an unlikely candidate.

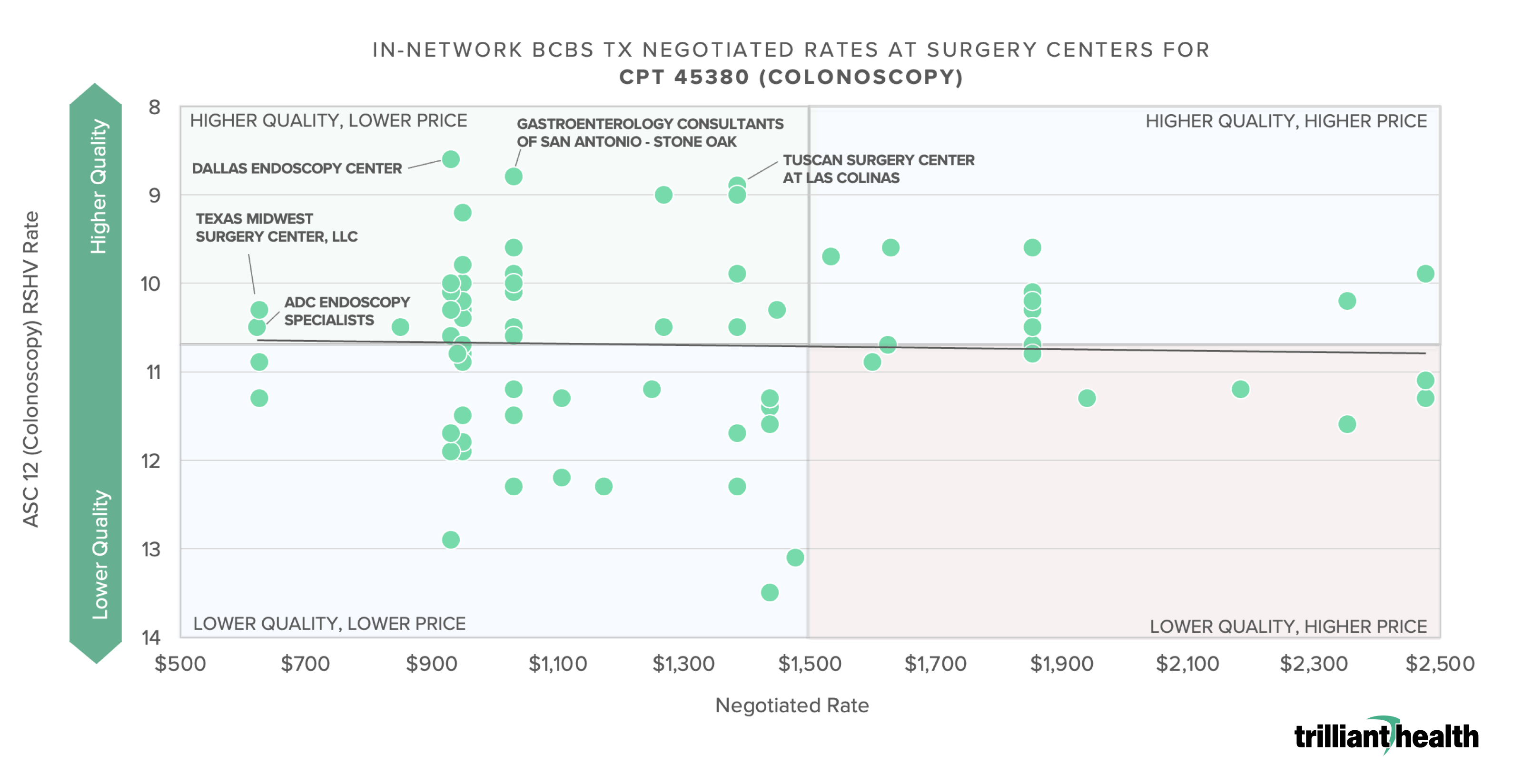

There is nothing that would unleash innovation in and transformation of the U.S. health economy more than the elimination of the tax deduction for employer-sponsored health insurance. Given the Federal government’s lack of courage to do something that is transformative and consumer-empowering, a first principles approach to the employer-sponsored health insurance would focus on enabling a beneficiary to access care that delivers value for money, beginning with understanding this data:

Note: Analysis was conducted using health plan price transparency Health Care Service Corporation negotiated rates (CMS definition) for surgery centers who billed code 45380 >250 times in 2022. (June 2023 file)

Source: Health Plan Price Transparency and Trilliant Health’s Provider Directory, and analysis of Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) Program data.

As noted in previous editions of Counterpoint, the idea of “steerage” to “narrow networks” would be the first casualty of a first principles approach to value for money.

2. Reliance on “state data.” In the song “War,” Edwin Starr sings, “What is it good for? Absolutely nothing, listen to me.” I could say the same thing about state data, and I have. While acknowledging that state data offers irrefutable proof to support my foundational thesis that healthcare is a negative sum-game, state data is as useful for strategy as teats on a boar hog. The first principle of an evidence-based strategy for everything, including healthcare, depends on probability, not history. As a result, the greater an organization’s reliance on state data for strategy or planning, the less strategic that organization is.

3. Electronic medical/health records. There are few more obvious examples of regulatory capture than the EMR/EHR industry resulting from the HITECH Act, which Bill Gurley of Benchmark Ventures recently explained in hilarious fashion. The fact that most U.S. hospitals utilize electronic medical records whose code base was developed in 1966 is a national embarrassment. The fact that the perceived value of these antiquated systems is their database structure, i.e., storing (structured) data, betrays the notion that they are facile for information exchange.

More importantly, the data that was important to store in 1966 has changed, which current EMR vendors have addressed simply by adding more fields to enter data, just like the Department of Motor Vehicles. Every farmer knows that lipstick on a pig is just that, which is why only corporate America thinks that an application layer with soothing colors can mask an aging platform saddled with technical debt. The savviest health systems know that the first principles of a clinical data warehouse is the capability to ingest a wide variety of data types and formats into a data store that feeds the EMR, not the inverse EMR-centric approach that includes only the data elements that your EMR vendor permits you to add.

4. Claims adjudication systems. Every health economy stakeholder knows about the oft-discussed “waste” in the U.S. healthcare system, and many know that studies suggest that administrative complexity represents more than $250B in annual waste.3 Few health economy stakeholders know that the original framework for calculating “administrative waste” in the U.S. healthcare system was a comparison to the cost of healthcare administration in Canada, perhaps the only time Canada has been a benchmark for anything in America.4 Instead of trying to build better claims adjudication mousetraps, reasoning from first principles would ask why claims administration is so increasingly complex that the global TAM is forecast to reach $136B by 2030.5

5. Patent protection for therapeutics and devices. Congress’ enumerated powers under Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution include the authority to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”6 Congress passed its first patent statute in 1790, established the U.S. Patent Office in 1802 and has Constitutional authority to implement specific patent protections with respect to therapeutics and devices, particularly patent duration.7 The fact that CMS is now negotiating drug prices suggests that current patent law related to life sciences is suboptimal, at least for purchasers. With the Federal government as a significant customer of the life sciences industry, reasoning from first principles might start with defining value for money, followed by shortening patent duration by therapeutic category or modifying provisions applicable to generics. Alternatively, patent law might borrow from copyright law to incorporate the doctrine of fair use to protect inventors of novel therapeutics and devices while also encouraging derivative works that accelerate innovation.

In 2005, I wrote the business plan for a large U.S. healthcare company to expand to the United Kingdom. I learned that the NHS couples compelling health policy with terrible execution. The United States is much closer to a government-based healthcare system than most will admit, but the NHS features that the U.S. system lacks are those that the American public – you and me – will really hate. I would submit to you that a rapid adoption of reasoning by first principles is the only thing that will prevent the U.S. healthcare system from ending up like England or Canada. If it does, by the time you realize you hate it, it will be too late.

Nick Saban, arguably the greatest college football coach in history, has stated that “mediocre people don’t like high achievers, and high achievers don’t like mediocre people.” Elon Musk is a high achiever who fires mediocre people as a matter of habit. When Musk acquired Twitter, he famously fired 80% of Twitter’s employees without a material impact on the performance of Twitter’s application.8 How many people in your organization would Musk fire? And how many would be missed?

Bill Parcells, who won two Super Bowls as the coach of the New York Giants, says that “you are what your record says you are.” Knowing your record – benchmarking, in health economy parlance – is the first step in “knowing what is true” to understand where you can and should improve. And the only way to make transformational improvement – as Musk has revolutionized the cost of space travel – is to employ first principles.9

Reasoning from first principles is hard, particularly for organizations that have never done so before. The only way to evolve from reasoning by analogy to reasoning by first principles is to follow a process like Coach Saban:

The process is really what you have to do day in and day out to be successful. We try to define the standard that we want everybody to sort of work toward, adhere to, and do it on a consistent basis. And the things that I talked about before, being responsible for your own self-determination, having a positive attitude, having great work ethic, having discipline to be able to execute on a consistent basis, whatever it is you’re trying to do, those are the things that we try to focus on, and we don’t try to focus as much on the outcomes as we do on being all that you can be.

A well-known hospital executive is fond of saying that the U.S. healthcare system works exactly as it is designed. What if he is correct? What if, as Pogo says, “we have met the enemy, and he is us”? What if the waste in the U.S. healthcare system results from too many mediocre people who are too lazy to reason by first principles?

Albert Einstein is credited with saying that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. When you finally tire of underwriting the administrative waste of the same industry conferences in Las Vegas and Orlando and Nashville and Chicago to hear the same people promote the same failed ideas, call me, maybe. I will help you understand your organization’s markets and market share and develop evidence-based strategies to optimize your business.

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)