Research

Cash Rates Are Often Lower Than Negotiated Rates for Common Hospital Services

November 26, 2025Study Takeaways

- Across 79 procedures and services, the reporting rate for 327 Texas hospitals for negotiated rates ranged from 40.4% to 66.8%, while reporting rates for gross charges and cash prices ranged from approximately 2.5% to 74%.

- Among four of five services analyzed, discounted cash prices were lower than negotiated rates.

- For CPT 45378 (diagnostic colonoscopy), negotiated rates ranged 24x with a median of $2,275, while cash prices show an 18x range with a median of $1,554, 32% below the median negotiated rate.

- CPT 95810 (sleep study) was an exception, where negotiated rates are the lowest overall with a median of $1,473, compared to a cash price median of $4,644.

Federal requirements now mandate that hospitals publish both their discounted cash prices and the rates negotiated with insurance companies for the same services. This obligation creates an opportunity to assess the true value of commercial insurance, which covers nearly 60% of Americans. For the same procedure at the same hospital, how do the rates that insurers have negotiated compare to the prices available to someone paying out of pocket (OOP)?

While transparency regulations have made this comparison theoretically possible, the practical reality is more complicated for inpatient hospital services. Because neither the physician nor the hospital nor the patient can know everything that will happen during an inpatient hospital stay, hospitals share "estimates" of the cost of services that patients are expected to receive. Because commercially insured patients are almost never responsible for payment of the full negotiated rate, much less billed charges, those patients have no incentive to focus on the total cost of those "estimated" services. As a result, patients rarely know or are even interested in how much a provider will receive as reimbursement for a particular healthcare service.

Moreover, since the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) does not allow a hospital to inquire about the ability to pay for emergency department patients, and since approximately 50% of all hospital admissions originate in the emergency department, hospitals often do not even inquire about a patient's ability to pay, much less routinely volunteer cash alternatives. Since commercially insured patients are the lifeblood of a hospital's financial results, the default mindset for reimbursement for inpatient hospital services is to bill health insurers for the services a patient receives, maximizing revenue from this population.

Background

Over the past 40 years, the Federal government has undertaken various measures to address the high cost of healthcare. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that between 2013 and 2018, commercial negotiated rates for hospital and physician services increased by 2.7% per year, compared to 1.5% for overall CPI-U, driven largely by provider market power and the limited price sensitivity of employers and consumers. While some of the factors that drive higher prices are intractable, policymakers and researchers have long believed that increasing patient and employer awareness of price and quality could bend the healthcare cost curve, although CBO disagrees.1 Until recently, the lack of access to healthcare prices left patients and employers without the ability to make informed decisions about the difference in price for the same service in a market.

Finalized in November 2019 and effective January 1, 2021, under the Hospital Price Transparency rule CMS mandated that hospitals publish machine-readable files (MRFs) containing standard charges, discounted cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges and de-identified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for at least 300 “shoppable” services. Hospitals are required to disclose negotiated rates with all commercial plans (group and individual), Medicare Advantage plans and managed Medicaid plans, though they only report in-network rates and are not required to identify bundled or capitated payment arrangements. While almost all hospitals published an MRF by November 2024, just 21% percent were considered fully compliant.2 Compliance remains erratic despite CMS enforcement mechanisms that include corrective action requirements and civil monetary penalties for non-compliant facilities.

Until a patient reaches their annual deductible, the distinction between negotiated rate and cash price can be meaningful. For example, a patient with a $6,000 deductible and $9,000 OOP maximum needing a hospital service with a $6,500 negotiated rate will be required to pay the entire amount OOP. If that same hospital's cash price for the service is $5,200, a patient who had not met any of his or her deductible would pay more for that service despite being insured.

Understanding both cash and negotiated rates provides essential information for anyone managing healthcare expenses or evaluating the value of their health insurance benefits, whether an employer or an employee with a high-deductible health plan (HDHP).

Analytic Approach

Hospital price transparency data were accessed through publicly available MRFs published under the Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule (45 CFR §180), which Trilliant Health has normalized and aggregated for more than 5,000 hospitals across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.3 Leveraging the aggregated and standardized MRF file, we examined negotiated rates, discounted cash prices and gross charges for the 70 required “shoppable” services in the original CMS transparency rulemaking process, along with six medical MS-DRG codes: MS-DRGs 190, 193, 216, 280, 291 and 870 for 327 hospitals in Texas. We examined the share of hospitals reporting by code along with the distribution of reported negotiated rates, discounted cash prices and gross charges for CPTs 45378 (diagnostic colonoscopy), 45380 (biopsy of large bowel via endoscope), 55770 (biopsy of prostate gland), 93452 (left heart catheterization for diagnosis) and 95810 (sleep study). While the analysis originally intended to include several common DRGs, it was discovered that the vast majority of hospitals in the analysis did not report discounted cash prices for the vast majority of DRGs.

Findings

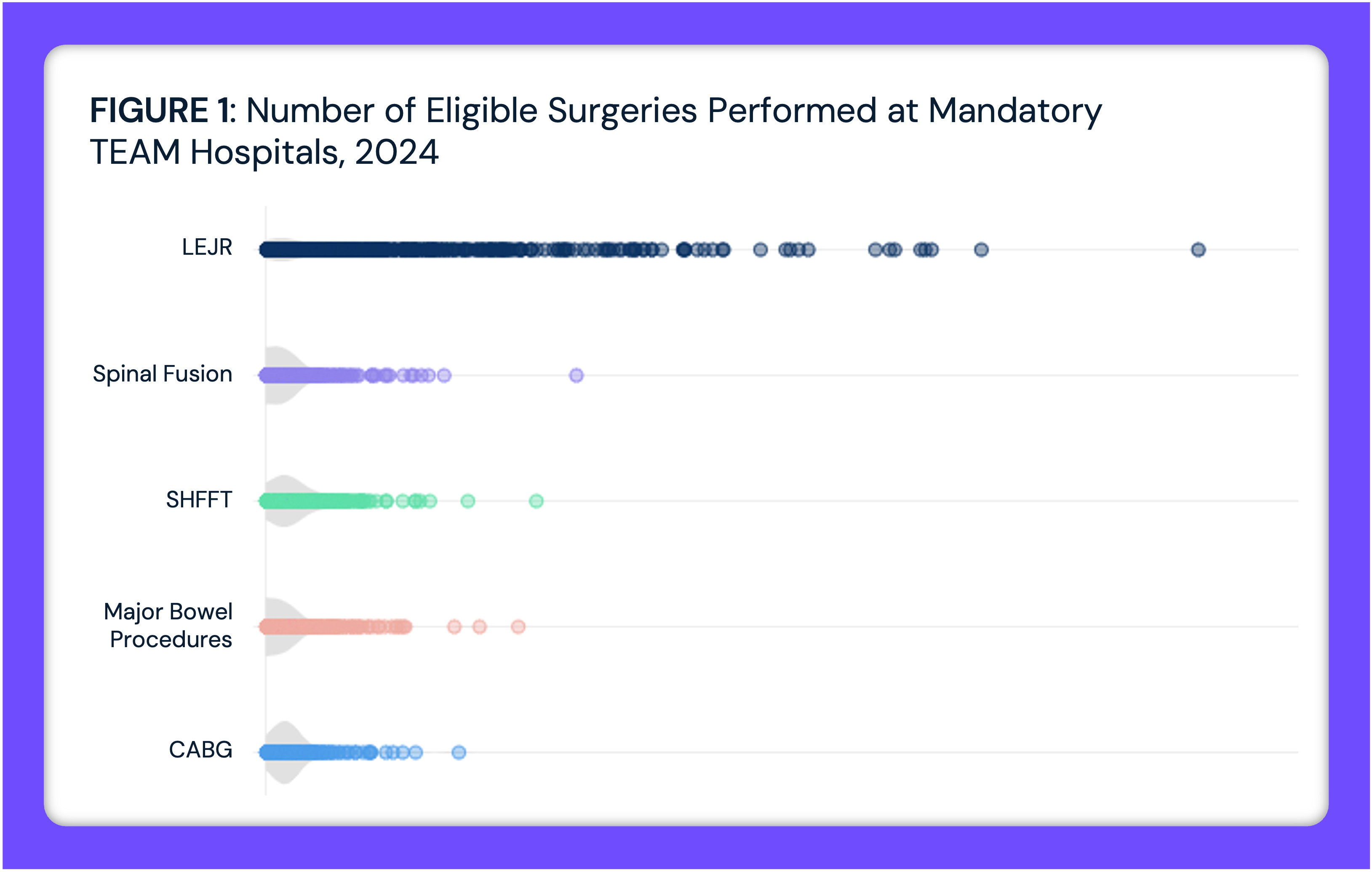

While 55.3% of hospitals in the analysis reported discounted cash rates for CPT codes together with negotiated rates, only 11.8% reported discounted cash rates for DRGs together with negotiated rates. Across 79 procedures and services, the Texas hospital reporting rate for negotiated rates ranged from 40.4% for routine OB services (CPT 59610) to 66.8% for a comprehensive metabolic blood panel (CPT 80053) (Figure 1). For gross charges and discounted cash prices, hospital reporting ranged from approximately 2.5% for CPT 59610 to 74% for a blood test to measure clotting time (CPT 85610). As Figure 1 reveals, hospitals report negotiated rates more consistently, if still far less than 100%, than they do either discounted cash prices or gross charges.

For diagnostic colonoscopies (CPT 45378) at Texas hospitals, negotiated rates across 100 hospitals from 116 health plans range by 24x, with a median of $2,275 (Figure 2). Across those same hospitals, discounted cash prices range by 18x, with a median of $1,554. Gross charges also range 18x, with a median of $3,889. As an example, at Memorial Hermann – Texas Medical Center, the median negotiated rate is $2,593 across 19 commercial health plans, while the discounted cash price is $1,543 and the gross charge is $4,817.

For large bowel biopsies via endoscope (CPT 45380) at Texas hospitals, negotiated rates across 107 hospitals from 121 health plans also vary widely, ranging 32x, with a median of $2,275 (Figure 3). Across those same hospitals, discounted cash prices show a 41x range, with a median of $1,402, while gross charges range 46x, with a median of $3,408. As an example, at Memorial Hermann – Texas Medical Center, the median negotiated rate is $2,593 across 19 commercial health plans, while the discounted cash price is $1,543 and the gross charge is $4,817.

For prostate gland biopsies (CPT 55700) at Texas hospitals, negotiated rates across 107 hospitals from 131 health plans demonstrate a similar variation, ranging 39x, with a median of $2,420 (Figure 4). Across those same hospitals, cash prices range by 116x, with a median of $1,832, while gross charges range 77x, with a median of $5,193. As an example, at Memorial Hermann – Texas Medical Center, the median negotiated rate is $2,797 across 19 commercial health plans, while the discounted cash price is $1,996 and the gross charge is $6,231.

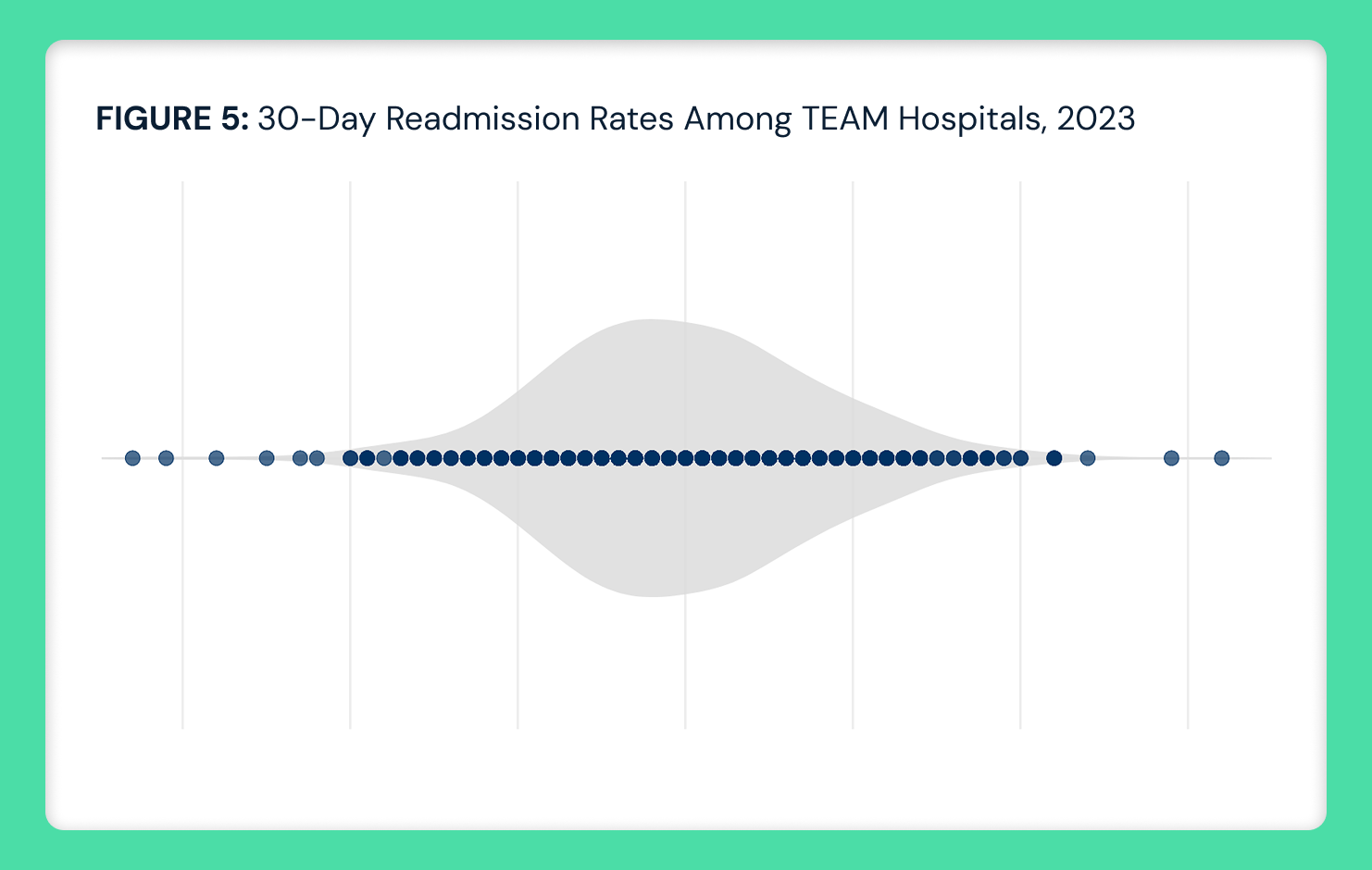

For left heart catheterization for diagnosis (CPT 93452) at Texas hospitals, negotiated rates across 138 hospitals from 208 health plans have slightly lower variation, ranging 17x, with a median of $9,773 (Figure 5). Across those same hospitals, cash prices show a 32x range, with a median of $5,499. Gross charges range 12x, with a median of $12,446. As an example, at Memorial Hermann – Texas Medical Center, the median negotiated rate is $13,771 across 18 commercial health plans, while the discounted cash price is $2,991 and the gross charge is $9,339.

For sleep studies (CPT 95810) at Texas hospitals, negotiated rates across 105 hospitals from 49 health plans also have slightly less variation, ranging 15x, with a median of $1,473 (Figure 6). Unlike other CPT codes analyzed in the study, discounted cash prices are higher than negotiated rates and reveal a wider range, with a median of $4,644 and a range of 29x. Gross charges range 14x, with a median of $8,425. Even so, the discounted cash price for CPT 95810 is below the negotiated rate at some hospitals. As an example, at Memorial Hermann – Texas Medical Center, the median negotiated rate is $1,833 across 10 commercial health plans, while the discounted cash price is $1,887 and the gross charge is $5,893.

Conclusion

Hospital price transparency has made both discounted cash and negotiated rates publicly available, but this information remains disconnected from actual payment decisions. Employers savvy enough to inquire about their broker’s financial incentives in recommending a health plan network are still prone to focus on the breadth of the plan’s provider network instead of the cost of that network. Patients with commercial insurance expect that they will not pay the entire cost of healthcare services, even if they don’t know or consider whether they could pay even less. Moreover, few patients know that hospitals offer discounted cash prices, and even fewer inquire about that price, so patient access representatives rarely disclose it. As a result, revenue cycle management in hospitals assumes insurance utilization by default, since uninsured patients represent a minor portion of hospital revenues.

For patients with HDHPs, understanding that cash prices often undercut negotiated insurance rates can be financially meaningful, particularly before reaching the applicable deductible. For all the reasons described above, leveraging that information to reduce costs depends almost entirely on the individual, as the information is challenging to access at the point of care. In any event, it is impossible for the individual to understand whether the discounted cash price is the optimal price since the individual is constrained within a network. Because hospitals contract with numerous health plans at a range of rates, the same hospital providing the same services with the same physicians can deliver high value in one network and low value in another.

Importantly, discounted cash prices are effectively irrelevant to emergent patients, who represent approximately 50% of hospital admissions. In addition to their focus on the anxiety associated with an emergent condition, patients presenting at the emergency department rarely know their diagnosis, making it impossible to search for specific procedure costs. Even for truly shoppable services where patients theoretically have time and options to compare prices, the complexity of understanding how deductibles, copays, coinsurance and out-of-pocket maximums interact with both cash and negotiated rates creates cognitive barriers that prevent informed decision-making.

However, the implications extend beyond individual patients. Even after an insured patient hits their deductible and becomes largely insulated from costs, employers who sponsor group health plans continue bearing the financial burden of negotiated rates that may exceed cash prices. When an employer's supposed "group negotiating power" yields rates higher than what an uninsured cash-paying patient would pay, those employers are effectively subsidizing unnecessary healthcare costs, a fact that every health economy stakeholder understands but continues to ignore.

In every industry in which consumers have benefited from price transparency, like airline travel, information is made available in advance of the transaction. While healthcare price transparency is “good” policy, maximizing the value of price transparency requires employers to utilize it before choosing a provider network. To date, health plan price transparency is utilized like pricing in airport retail shops, where the traveler can compare the cost of a $5 bottle of water and a $6 cup of coffee.

Until hospitals, insurers and policymakers close the gap between data availability and decision-making utility – ensuring that comparative pricing information reaches patients and employers before they need it – transparency regulations will remain a theoretical tool rather than a practical solution for the Americans whose financial wellbeing increasingly depends on making informed healthcare decisions.

- Studies

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)