Counterpoint

Hal Andrews | September 6, 2023Understanding the Funny Math of Value-Based Primary Care Clinics

Much has been written in the last five years about “reimagining primary care,” mostly by people who have never operated a primary care physician practice. Experienced operators know that the margins for the most efficient primary care practice are in the single digits; most health systems lose at least $100K per year per employed physician, hoping desperately to “make it up in volume,” i.e., downstream referrals.

As we have written previously, “value-based primary care” is a reimbursement scheme that can be extraordinarily profitable under the following immutable conditions: the practice takes full capitation, for at least 50,000 “covered lives” in a metropolitan area, like Miami-Dade County or Las Vegas, from a single payer, preferably a Medicare Advantage plan, like Humana or United. Physician-led primary care practices like HealthCare Partners, MCCI and WellMed have executed this model expertly for decades.

Why, then, have leading U.S. venture capital firms recently pursued a business model for their “holistic, consumer-centric, next-generation” primary care models that is almost completely opposite of this proven formula? To be fair, these venture capital firms can legitimately claim to have “reimagined” primary care; never before has a primary care strategy lost hundreds of millions of dollars.

1. Q2 2023 CVS earnings call (https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2023/08/02/cvs-health-cvs-q2-2023-earnings-call-transcript/)

2. Through 3Q May 31, 2023 (PowerPoint Presentation (q4cdn.com))

3. Year ended December 31, 2022 One Medical Announces Results for Fourth Quarter and Full (globenewswire.com)

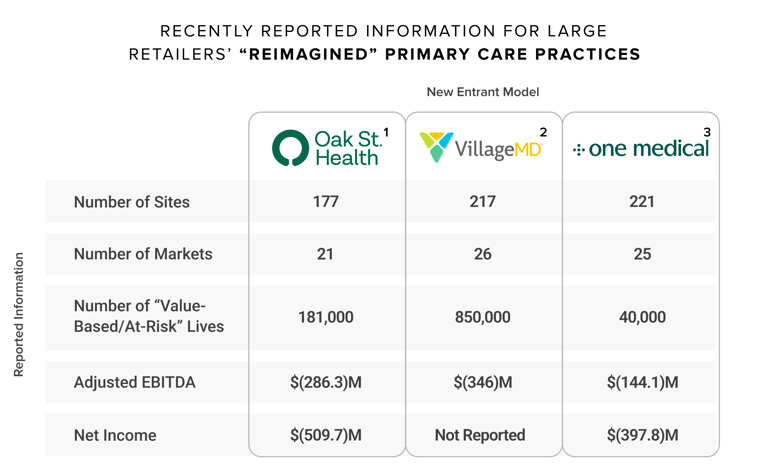

Even more curious is why retailers with no previous experience in operating primary care practices have become the “go-to” exit strategy for these “next-generation” venture-backed companies losing hundreds of millions of dollars delivering “holistic” and “consumer-centric” primary care, often in a closet-like space in a pharmacy or over an iPhone.

Anyone who has ever operated a primary care practice knows that there are two ways to be profitable:

- take full capitation for as many patients as possible, and then control referrals for ancillary services as much as possible;

- provide as many in-office ancillary services as possible, and then make as many self-referrals as the Stark Law allows.

How could any board of directors approve paying any purchase price, much less billions, for a “next generation” primary care business model that is clearly financially unsustainable on a standalone basis, just like most primary care physician practices? (Editor's note: This was written prior to the news of the resignation of Rosalind Brewer from Walgreens on September 1, 2023.) The implicit size of the patient panel in these “next generation” primary care practices is one clinic per 1,700 patients, suggesting that the United States only needs 193,705 more of these “holistic, consumer-centric” clinics to meet the needs of every American. That, of course, is absurd, which is why that must not be the plan. If it were, then the already severe shortage of primary care physicians would increase by ~25% since a typical primary care patient panel is 2,300.1

Why have Amazon, CVS and Walgreens invested billions of dollars to acquire enterprises that reliably lose hundreds of millions of dollars per year? What do the world’s largest retailers – the truly consumer-centric companies – know that the rest of the health economy doesn’t know?

In a word, pharmacy.

According to the Drug Channels Institute, total pharmacy industry prescription revenues were $547.9B in 2022, which is almost 50% of total U.S. hospital spending.2 The $1.3T in hospital spending in 2021 was divided among more than 5,000 hospitals, with HCA, the largest hospital operator, leading the market with a 4.4% share. In comparison, CVS had a 25.6% share of the prescription revenue segment in 2022, and the five largest U.S. pharmacy operators – CVS, Walgreens, Cigna, UnitedHealth Group and Walmart – had an aggregate 63.6% share.

The only way that these “next generation” primary care models can be profitable is by selling ancillary services to patients, in this case, pharmaceuticals.

The large retailers know that the Stark Law doesn’t prevent their “holistic, consumer-centric” clinics from prescribing pharmaceuticals to their patients and offering convenient delivery, whether a few steps down the store aisle or directly to the patient’s home. These retailers also know what other goods – cosmetics, toys, grocery items, etc. – their customers add to their shopping basket before checking out.

What does that mean for traditional healthcare providers?

What health systems consider fragmentation of primary care for “their” patients is what retailers believe is disintermediation on behalf of “their” customers. Merriam-Webster defines disintermediation as “the elimination of an intermediary in a transaction between two parties.”3

Since disintermediation only happens when there is a transaction between a buyer and a seller, large retailers can only disintermediate healthcare with respect to the goods and services that they provide; however, they want to do that 100% of the time. Amazon, CVS, Walgreens and Walmart are without peer at winning the hearts and minds of the consumers in transactional settings, particularly for commodity goods and services. Of those retailers, Amazon is particularly effective in eliminating any friction between it and “its” customer for any service or good that it provides.

Consequently, these retailers have no incentives for – or experience in – “care coordination” with respect to services that they don’t offer. For example, One Medical had 836,000 “members” at December 31, 2022, but only 40,000 – or less than 5% – were “at-risk.” Translation: One Medical has no financial interest in “care coordination” for the 796,000 members who are not “at-risk,” although they have an obvious interest in having Amazon Pharmacy deliver every single prescription written by a One Medical provider.

On the margin, the incentives of large retailers are for their employed providers to order therapeutics over diagnostics, unless those diagnostics might result in a therapeutic. In turn, these retailers are – at least for now – indifferent to the “winner” of the referrals for those diagnostic and procedural transactions they don’t provide.

Finally, the “membership” aspect of these “consumer-centric” primary care models is structurally transactional, not longitudinal. By openly advertising the price for a primary care or virtual visit, these retailers will increasingly commoditize what has historically been a relationship-driven – and price insensitive – business model. The implications for traditional primary care providers specifically and care coordination generally are momentous.

.png)

.png?width=171&height=239&name=2025%20Trends%20Report%20Nav%20(1).png)