A History of Value-Based Care Programs Leading Up to the New Enhancing Oncology Model

Value-based care (VBC) is a polarizing and ambiguous concept in the U.S. health economy. In theory, VBC is a simple framework to exchange “value for money” or, in other words, reimbursing for care based on the quality and efficiency of a health outcome. In practice, VBC is enormously complicated for many reasons, including the absence of a true understanding of the total cost of care for a patient's journey. Again, in theory, health plan price transparency holds the promise of quantifying the cost of a care journey, although measuring outcomes may remain elusive.

Understand your organization's risk with our interactive EOM Performance Estimator.

A Brief History of Value-Based Care Prior to the Oncology Care Model (OCM)

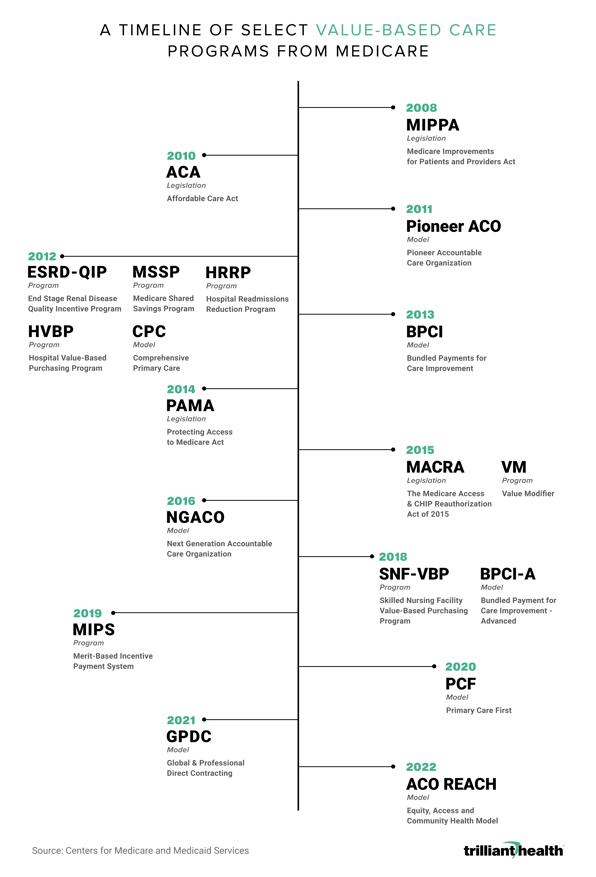

VBC entered the policy and consultant lexicon in 2005 with the Physician Group Practice Demonstration created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In 2008 CMS established the End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program (ESRD-QIP), the first program where payments were tied to quality measures.1,2 The Affordable Care Act expanded VBC after it established the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to design and test new VBC programs, the largest of which has been the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). Proof of the elusive nature of VBC can be found in the seemingly endless number of programs designed by CMS, which are depicted in this graphic:

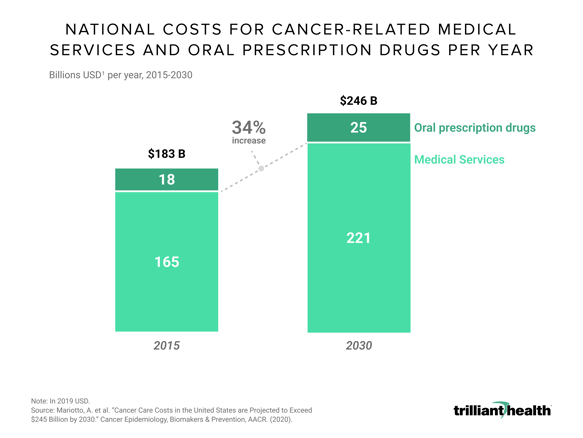

Despite the quixotic nature of VBC to date, CMS and other payers continue to pursue it, particularly with respect to cancer. While tremendous progress has been made in cancer outcomes with improved screening and new treatments over the last 20 years, annual costs for cancer-related services and drugs are projected to reach nearly $246 billion nationally in 2030, representing a 34% increase since 2015.3 This growth is driven by the aging population, innovative therapies that are life-extending but also more expensive, and high variation in care between different populations and cancer types.4

The Oncology Care Model (2016): Mixed Results

In 2016, CMMI established the first oncology-specific alternative payment model, the Oncology Care Model (OCM), the primary focus of which was improving care coordination and patient outcomes. As is typical of VBC programs, the results were mixed. While spending was reduced in certain instances, there were no significant changes in emergency department visits or hospitalizations, which are both quality indicators and key cost drivers. As a result, CMS lost over $375 million in the first half of the program after accounting for operating and incentive payments to practices, and clinical results varied significantly by tumor site, disease severity, and patient risk.5

Participating in the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM): Worth the Risk?

CMMI hopes that the Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM), launching in July 2023, will remedy certain shortcomings of OCM. Most importantly, EOM targets a smaller patient cohort of higher-risk patients with common tumor types and includes mandatory care management programs and expanded data reporting, both clinical and patient-reported. Notably, per beneficiary per month (PBPM) operating payments are significantly reduced, and participating practices must accept downside risk from the outset.

The fact that CMS has yet to finalize the 81-page EOM payment methodology document is a testament to the complexity of the program, leaving practices with little insight into the expectations of care and financial goals for their beneficiaries. Additionally, risk-sharing arrangements proposed by EOM are not true shared risk between provider and payer, as 100% of the risk resides with the EOM participant, exposing providers to financial penalties payable to CMS.

Ironically, the financial and technological investments required to participate in true risk-based VBC programs in a fiscally prudent manner are likely to require increasing consolidation of physician groups and other healthcare providers, setting CMS’s payment policy initiatives against the antitrust policy of the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission.

The combination of EOM’s limited scope and increased financial risk may create significant headwinds for this program. Reduced monthly payments, unbalanced risk allocation, increased reporting requirements and implicit need for financial reserves to pay penalties will likely discourage participation, especially by smaller, independent practices with limited resources to invest in information systems necessary to comply with EOM’s reporting requirements.

Thank you to Cindy Revol for your research support.